ARTS: The Petit Paris And Me

▼

Correcting Life’s Little Mistakes ◆ by Tom Roznowski

Childhood is about entering life through doors left unlocked. I was taught from an early age that America has more doors with light shining under them than anywhere else in the world. Growing up here, you sense it must be coming from the sun shining on a distant horizon: the satisfaction of a good day past or the anticipation of the new day ahead.

A few years ago, there was a historic analysis done of the so-called happiness index. It indicated that collectively Americans felt the greatest sense of optimism and security in their lives during the year 1957. Statistical guru Jeff Sagarin tells me it’s even more definitive than that. He focuses on the resonance of one single day: October 4, 1957. That Friday saw the launch of the Sputnik satellite into space, the television debut of Leave It To Beaver, and a travel day for the Milwaukee Braves and the New York Yankees as they battled in an epic seven game World Series. (I should mention here that the previous week, “That’ll Be The Day” by Buddy Holly and the Crickets was the hottest selling single in America).

Curiously, that year has also been cited by long-time New York City residents as the finest the city ever felt during the 20th Century. Urban environments are by their very nature dynamic and complex, so calculating the high point of their evolution is at best a doubtful exercise. That said, in 1957 New York City Miles Davis was recording Miles Ahead, Madison Avenue had real Mad Men, and My Fair Lady was playing on Broadway. Oh yea, and Mickey Mantle was 25 years old as he trotted out to play center field for the home team. I consider this some fairly persuasive evidence.

My own childhood was spent in the post-war suburbs of Albany, New York, which in 1957 was the capital of the most populous state in America. New York would be eclipsed by California in that regard while I was still in grade school, but culturally and commercially the Empire State remained the nation’s epicenter for a while after that. This was another random stroke of good fortune for me. California would come to reflect America in the last quarter of the 20th Century, when we were obviously not at our best.

Friday, October 4, 1957, would have found me walking home from school along another Madison Avenue, the main commercial district for my neighborhood. Albany was about 135 miles from New York City, a far greater distance back then. I don’t think I’d insult my hometown by remembering it as comparatively provincial. Still, Albany was close enough to absorb occasional cultural resonance from the great city to the south. If one could have ever devised an antenna expressly for that purpose, I believe it might have been planted on the roof of 1060 Madison Avenue.

I always had a fascination with the building as I passed by it back then. But as a small child, my curiosity would have only been met by a locked door. So now it’s left up to me, over 50 years and 700 miles distant, to uncover the secrets of what lay hidden on the other side. That light beneath the door is dim and smoky. Press an ear close to hear the music and chatter, occasionally punctuated by a loud laugh and the clink of plates and glasses. Inhale the aroma of strange cooking and imagine some big fun for adults inside.

1060 Madison Avenue in Albany, New York was the address of the Petit Paris. I remember it as an undistinguished stucco building with weeping ivy and a plain wooden sign. Modest elegance, you might say. Tiny windows were set to either side of an arched oak door; an indication that daylight held little sway with the business going on within.

The Petit Paris, Albany, New York

■

A restaurant—that was about all it revealed to me. The dinner menu for was framed in a showcase above the mail slot. It featured Flaming Sword Coq-au-vin, Escargot, and Crepe Suzette: generic French cuisine for post-war America. I would guess that more than a few of the customers had served in France during the war. Having experienced the country at its worst, perhaps some veterans were eager for a chance to change their impressions. A skilled chef and a full bar might help there.

So would the movie Gigi, which would soon premiere to rave reviews, eventually winning the Best Picture Oscar. Set in the vibrant Paris of the 1890s, Gigi was originally intended by Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner to be follow-up to their tremendously successful run of My Fair Lady on Broadway.

Turned out they took a detour on the way to the stage. Hollywood producer Arthur Freed essentially made the pair an offer they would not refuse, yet one more victory for California over New York. Already in 1958, New York City and Brooklyn had lost major league teams to the West Coast. To some, Gigi justified the means by grossing over four times the film’s bloated budget.

This was essentially the same method of persuasion used to dispatch the Petit Paris. One afternoon as he was wiping down the bar, owner Mike Flanagan received an early visitor. He inquired whether the place might be for sale. Mike named an unreasonably high price, figuring it would discourage a merely curious buyer. One month later, the visitor returned and they shook hands on the deal. On July 3, 1973, the Petit Paris closed. Within two months, it was bulldozed to make way for a supermarket. I was working a summer job in the Catskills and heard the news in a phone call home.

So I never did walk through that big oak door and I guess I must have regretted it ever since. On a whim recently, I entered “Petit Paris Albany” into the Ebay search engine. Lo and behold, there it was. An old unused postcard revealed what was waiting on the other side in that smoky light.

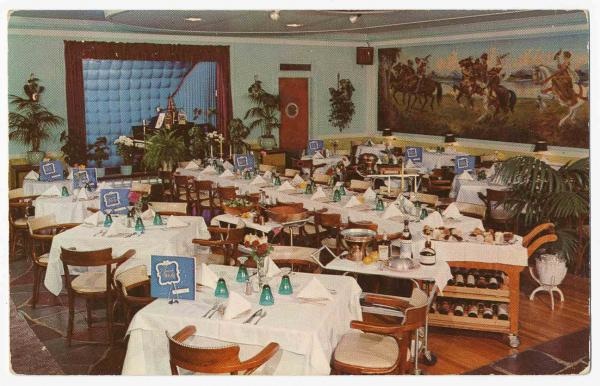

The photograph shows white linen tablecloths with napkin tents and champagne buckets. A huge painted mural on one wall depicts something regal and historic. Soft blue colors dominate the club. I imagine Maurice Chevalier’s top hat in Gigi was a similar shade.

And then, an unexpected surprise; the kind previously locked doors can reveal when you get past childhood. An elevated stage for live performance complete with velvet curtains, a baby grand, and huge potted palms to either side. Wonder of wonders, it turns out the Petit Paris was actually a swanky nightclub.

Looks like there would have been just enough room on stage for a five piece combo. Why, after few phone calls a long weekend of dates featuring Miles Davis and his road band might be arranged. Maybe the core group he’d use for the Kind of Blue sessions. Do you think Coltrane would make the trip? Friday night. I’d order an appetizer, their best vintage, the Chateaubriand, saving just enough folding money to bribe the band into playing “My Funny Valentine.” And the waiter would keep filling my glass.

After the last set, I’d step out into the brisk October night and hail a cab. Union Station, I tell the driver. I check my wristwatch. Last train to Grand Central. Game Three of the World Series is tomorrow afternoon in Yankee Stadium. I have box seats along the third base line.

Sure, I already know the outcome. That’s why I’ve set my dream date for New York City one year later: October 4, 1958. Game Three on that Saturday will still feature the Yankees and the Braves with Mantle in center. Only this time, the Yankees win in seven.

A short stretch of perfection; just enough to make me believe that there are no locked doors; that every knob I reach for will turn gently in my hand.

▲