LETTERS: If You Brand Too Deep, The Worms Will Get In

Inhabiting, Crossing-Over & Crossing-Out Textual Space in Crispin Glover’s/W.M. Baker’s Novel, “Oak-Mot” (1868 & 1991) ◆ by Christopher Martiniano

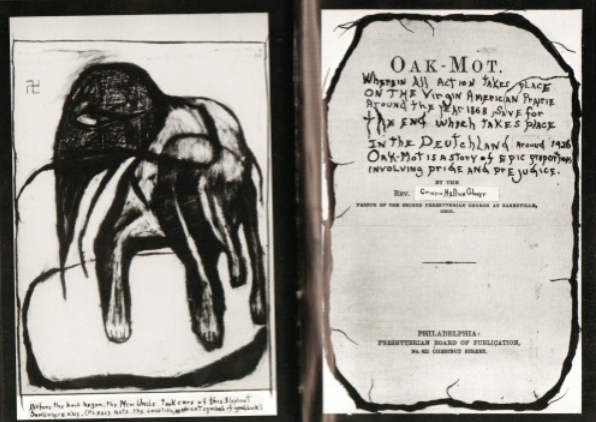

The 1868 American novel, Oak-Mot written by the Right Rev. William M. Baker, Pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, is largely forgettable and mostly forgotten. Baker’s sentimental story sprawls, while its family ranges and ultimately settles a new home in a place called Oak-Mot. Baker’s original book, in the hands of actor, artist, filmmaker, author, songwriter, singer and provocateur, Crispin Hellion Glover, is radically transformed. Glover published his version of Oak-Mot almost 125 years later in 1991, sharing with the original novel many of the same characters, much of the same text, many of the same chapter headings as well as the same typeset, printed pages. Besides these similarities however, Glover re-inhabits and radically transgresses Baker’s traditionally bound novel and transforms it into a worm-ridden, postmodern palimpsest. Glover’s palimpsest, however, operates much differently than the traditional definition of it used by manuscript scholars and historians.

■

Historically, a palimpsest is a parchment or other writing surface on which the original text has been effaced or partially erased, and then overwritten by another. In Glover’s palimpsest, however, he takes over the original pages, its characters and ultimately the story with what Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) called in 1987 his “hierographics.” Without total erasure, Glover effaces the original text with thin tendrils of India ink that sprawl across the page and reframe Baker’s pages. These spindly black cross-outs and white outs cover over many of the original words and passages; scrawled, handwritten words, sketches, and scratches that couple with the ominous, re-worked photography and illustration to recolor Baker’s novel. In an act of near total, palimpsestuous (to borrow a wonderful word from literary critic Sarah Dillon) effacement, the foundation of Baker’s Oak-Mot can barely be seen beneath the rising blackness of Glover’s Oak-Mot.

Due to these hierographics, the surfaces of Baker’s original novel are nearly unrecognizable. Describing his own method in an interview with The Ryder, Glover speaks of the organic growth of a narrative, from page-to-page beginning with a scrawl and ending with a coherent story. He says,

Old books from the 1800s…have been changed in to different books. They are heavily illustrated with original drawings and reworked images and photographs…. I was in an acting class in 1982 and down the block was an art gallery that had a bookstore upstairs. In the book store there was a book for sale that was an old binding taken from the 1800s and someone had put their artwork inside the binding. I thought this was a good idea and set out to do the same thing…. I worked a lot with India ink at the time and was using the India ink on the original pages to make various art. I had always liked words in art and left some of the words on one of the pages. I did this again a few pages later and then when I turned the pages I noticed that a story started to naturally form and so I continued with this.

By his own admission, Glover originally began drawing and scrawling within found books as a means to create and house his own pictorial art — framed “inside the binding.” Oak-Mot and 12 other Glover books as well as his sculpture were first displayed at LACE in late 1987. And on a Late Show with David Letterman episode a few weeks before this exhibition, Glover showed Letterman his book Rat Catching in its original, pre-published form. Letterman asked, “Are these actual, earlier publications?” and Glover answered — or rather, nervously stammered through the answer — “I remade them.”

According to a press release by LACE in 1987, Glover’s was a “Bookstore Exhibition” and his books were “created within an existing book altered by his writing and imagery interwoven into the original narrative, the works included found photographs, bookplates and the author’s own system of hierographics”.

Of course fiction is a form of art but but Glover’s narrative art insists on the difference between using a book as a medium to create pictorial, sequential or sculptural art and creating a palimpsestuous narrative in novel. But what is it? Oak-Mot is a book in form if not a novel but more importantly, a palimpsestuous hybrid narrative of text and graphic, found object and invention, emergence and burial. The coherence of the narrative, outside of plot derives from Glover’s hierographics that create fairly simple thematic and affective juxtapositions by blocking out or burying much of the text from the original 220-page novel.

Recently described in an interview as “whimsical vagrancy,” Glover’s re-habitation of Oak-Mot, like his other books, radically re-shapes and wanders over the original text, often supplementing it as much as he builds over and conceals it, then quickly leaving that portion of the structure to begin a new one. What makes Glover’s Oak-Mot particularly “vagrant” or homeless and ultimately unsettled is his rebuilding the novel with patches and layers of lacunae — or holes and pits in the Latin sense of the word. This is not to say that the text is constructed from negativities or absences but that each page’s surface is a ruined yet annexed landscape of pits, ditches, channels and gullies in which parts of the original text are buried or layered over by new textual/graphical formations. The first three pages of Glover’s palimpsest, for example, are pages 7, 10 and 17 of Baker’s original. This new sequence, undermined by traditional lacunae or absence, is narratively cohered by the layering of Glover’s hierographics that connect and juxtapose passages of text that shockingly shift to new episodes and/or introduce new characters and locales.

Glover’s mark-outs or burials of the original grow organically out of and in the text, the various spindly lines emanate from the amoebic, black boxes as tendrils. These many black scrawls and scratches act more like worms or better still, channels or trenches that mark the path of a worm through Baker’s original prairie. The only recurring text of Glover’s Oak-Mot that originates in Baker’s is on page 94. Glover carries the macabre, “The worms will get in. They will get in” through his version of Oak-Mot. It occurs again at the bottom of page 101, “The worms will get in” and at the bottom of page 188 in very large, horrific and elongated letters, “The worms will get in”. The first of six selections from Oak-Mot that Glover reads for his accompanying CD ends with the dramatic flourish of the music on an echoing guitar’s E minor chord and Glover’s whisper repeating, “They will get in. The Worms will get in.”

Worms are of course hermaphroditic, each individual possessing both male and female reproductive organs, thus making them perverse mirrors of themselves from one end to another. Glover’s worms too, are hermaphroditic in the metaphoric sense, being both textual and graphical. Pages 58-59, for instance, show the worms channeling across the surface of the page, over the reworked photograph and encircling the text, burrowing across the gulley separating the two pages connecting Adry, the new Uncle and Prosy, culminating in the text, “Adry is a little wrong in his mind” just below the ghost-like image above it (59). Glover worms, like real ones, devour the surface of Baker’s original novel and deposit or secrete black residue upon his pages, building up new surfaces that bury and/or annex the newly cohered text of the restructured Oak-Mot. Glover’s worms operate as palinodes, which means “recantation” or literally from the Greek, “to sing again” as Glover re-narrates Baker’s original text.

Editor’s note: Excerpted from a longer essay that was presented at Indiana University’s conference, “Collections & Collaborations: Occupied: Taking up Space and Time”, March 22, 2012.

▲

The Ryder, February 2013