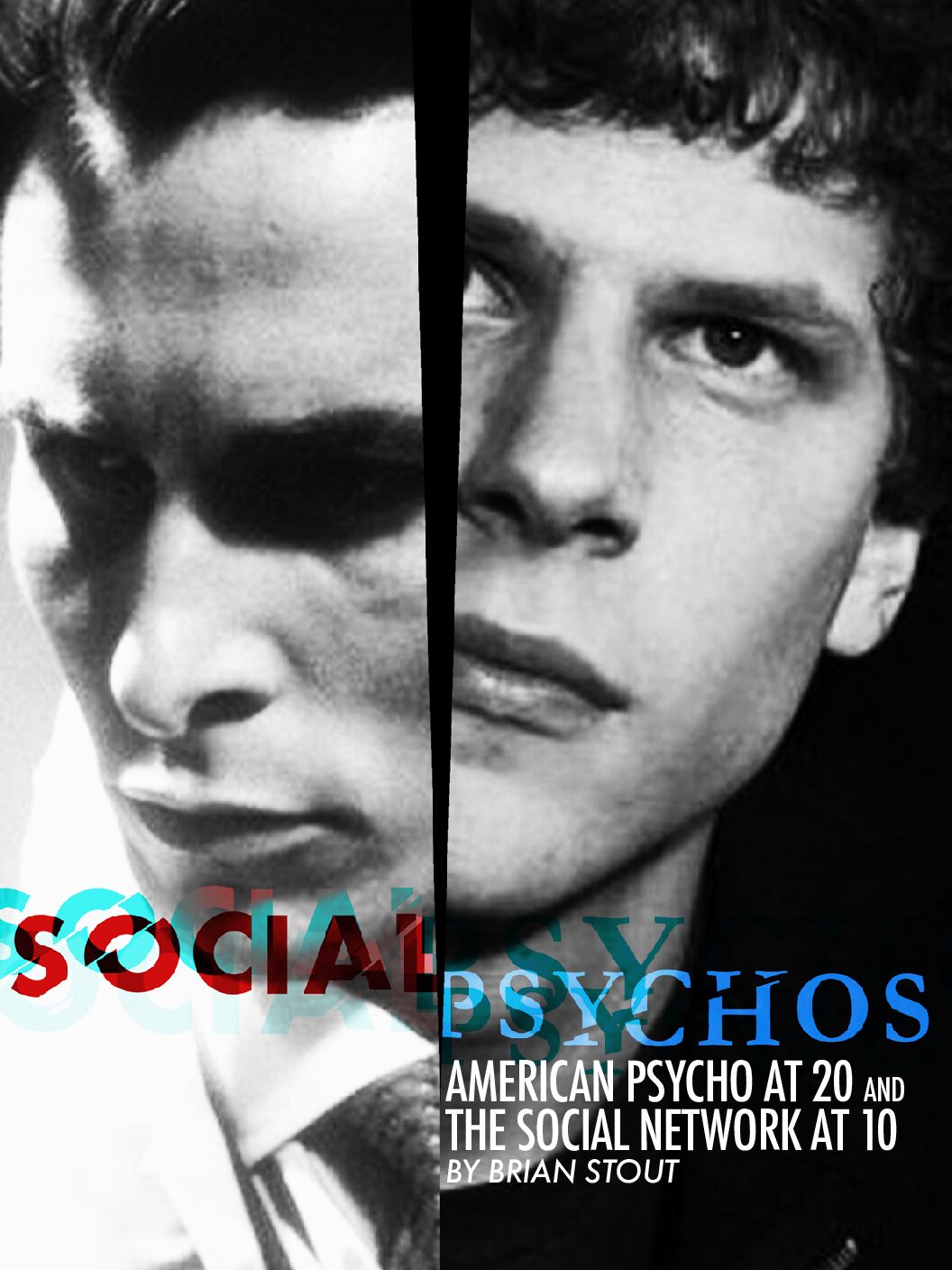

Social Psychos

American Psycho at 20 and The Social Network at 10

By Brian Stout

Easily lost in the midst of this chaotic year, two cinematic landmarks of toxic masculinity had milestone birthdays–David Fincher’s increasingly relevant The Social Network turned 10, and Mary Harron’s adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ 1990s lightning rod novel American Psycho turned 20. Is there a connection between a 1980s yuppie losing his grip on reality, coping through serial murder, and the ruler of a social media empire that has been blamed for playing a role in the deepening divide in the nation, potentially interfering in the 2016 election, and making your holiday meals more uncomfortable?

Both films are adaptations of noteworthy books–Bret Easton Ellis’ novel was so controversial that it was dropped by its initial publisher Simon & Schuster (Vintage eventually put it out), and the source for The Social Network was a book that relied heavily on accounts from Eduardo Saverin, one of the displaced founders of Facebook. American Psycho provides a critique of late 20th century greed and The Social Network offers a snapshot of the post-dot com landscape and our time in this century. In many ways, the Wall Street Masters of the Universe are quite similar to the toxic Tech Bros from recent revelations. Both films call attention to how the concerns of the elite–wealth and status–haven’t changed much; those who feel they are just outside of that exclusive circle are driven to extremity by their desire to achieve the acceptance of those around them.

Zuckerberg and Bateman are already members of these rarefied groups, but they are still outsiders. Bateman is a blueblood, but he is dismissed by those around him and seen as deeply uncool. By his own admission he is a concept, not a real person. He does not exist. Zuckerberg’s lack of acceptance into a Final Club and rejection by women drives his purpose. And access to these exclusive clubs does not produce happiness or satisfaction for either.

The novel that inspired Harron’s film was either a misogynist fantasy or a savage critique of the greed-is-good mindset or both, depending on who’s asked, but the film adaptation presented a more nuanced take that pushed the satire forward and left most of the gruesome, at times unreadably detailed, violence against (mostly) women off screen without sacrificing the critique of the 1980s Wall Street Masters of the Universe. By emphasizing the dark comedy over the horror, Harron was able to distill the point Ellis wanted to make into a more accessible work without diluting it, and anchored by a phenomenal performance by Christian Bale, American Psycho has outlived its mixed reviews and modest theatrical success to become a cult classic.

Conversely, The Social Network enjoyed near universal acclaim from the start, a box office hit nominated for eight Oscars (including a Best Actor nomination for Jesse Eisenberg) and winner of three. And while it is based on a book that purports to be non-fiction, Zuckerberg claimed “they [the filmmakers] made stuff up that was hurtful,” but that’s unsurprising given how he comes off in the film, burning bridges, exacting revenge when he felt slighted or jealous, and potentially orchestrating situations that made him appear justified in cutting his business partners loose.

We learn about our protagonists through different means. Bateman provides an incessant voiceover describing his fitness and wellness routines and a little of his mindset, but Zuckerberg becomes known mostly through his actions and others’ responses. He rarely voices his own opinion about anything, except to assert his own brilliance.

Bateman and his peers never seem to work; although they go through the business motions and are all Vice Presidents according to their similar-looking business cards, which provides one of the best running jokes. Their interchangeability and uselessness are the point. Meanwhile, Zuckerberg and team devote their lives to The Facebook. A less complex film would have set him up as the success story from modest means, but The Social Network does not settle for that; Fincher sets his sights on Zuckerberg’s motivation and ambition. We should want Zuckerberg to succeed, outsmarting and outperforming the bluebloods, but his cunning and casual misogyny make it difficult, and the film has no interest in him as a hero.

Both films call attention to how the concerns of the elite–wealth and status–haven’t changed much. Zuckerberg and Bateman are already members of these rarefied groups, but they are still outsiders. The most exclusive and hippest restaurants elude both of them.

In addition, the leads’ motivations are closer than they appear on the surface. Throughout American Psycho, people are constantly mistaken for each other and asking out loud if they see 1980s icons like the current President, or his wife at the time. Bateman even learns that many of his peers dislike him because they think they are talking about him when they are actually talking to him. These mistakes set the stage for his ability to get away with murder. His status affords him the luxury of being able to commit and cover up his crimes. When he goes to clean up a murder scene, it appears that the realtor has beaten him to it, seemingly afraid to risk the notoriety of showing a property where multiple murders occurred.

Zuckerberg is also trapped in a sense, fighting against the anonymity of being just another Harvard student, angling for how to stand out among a sea of perfect SAT scores and summers spent making money on oil futures. The now classic opening scene sets the tone for his portrayal. His monologue betrays his obsession with proving himself by gaining an entree into a Final Club at Harvard. He is barely engaging his date, Erica, critiquing her words, insulting her education, and later critiquing her body and her family name in a blog post right before he starts the genesis of Facebook, a site where users rate women’s physical attractiveness.

Despite Bateman’s life of expensive meals, easy drugs, Broadway shows, and exclusive nightclubs, he and his friends never seem to fit in when they go out. They party in their business suits around fashion victims at nightclubs they would be turned away from otherwise. Bateman bought his way in, but the most exclusive and hippest restaurants elude him, just as Zuckerberg never got punched for a Final Club. He tries endlessly to get a reservation to no avail throughout the film, and he chops up rival Paul Allen, who has been to Dorsia, with an axe, screaming about how he won’t be able to get a table now. Both Bateman and Zuckerberg are still on the outside looking in, despite Bateman’s apparently born-on-third-base success and Zuckerberg’s relentless drive to be known as the sole creator of Facebook. Zuckerberg gave us a place to see our friends while cutting ties with all of his. Bateman runs in elite social circles, but is seen as a “loser” and a “dork” by peers, and pontificates passionately about the deeper meaning of glossy pop songs by Genesis and Huey Lewis and The News.

It could be argued that they both deal with the situation by acting on their worst impulses–Bateman kills peers and others, Zuckerberg (at least according to the film) exacts revenge on his friends and colleagues by cutting them out of deals through set-ups that lead to seemingly justified firings. The film implies that these are at least partially motivated by jealousy, since Eduardo Saverin was “punched” for a Final Club, while Zuckerberg was not, despite his work on The Facebook. He may have called the police to get Sean Fanning in trouble to create a reason to show him the door.

The films also share an essential disdain or indifference to women. American Psycho’s women are spoiled caricatures for the most part, except for the somewhat sympathetic portrayals of Patrick’s secretary and a prostitute who meets an unfortunate fate. Aside from Erica, women in The Social Network for the most part are the unattainable prize that motivates, as Napster founder Sean Fanning notes he started the company to get a girl’s attention in high school and, in one scene, shrugs off his Victoria’s Secret model date. Once attained, the women in the film are for the most part seen as unstable or pretty accessories, such as the portrayal of Saverin’s girlfriend. Bateman expresses little more than disdain for his girlfriend and suspects her of infidelity while sleeping with and sometimes murdering whomever he chooses.

By the end of American Psycho, Bateman has murdered many (Harron made this clear in subsequent interviews, despite the somewhat open end that let audiences and critics to question what really happened) and even confessed to his lawyer, but it is evident that no one believes he is capable of such horrific acts. He is too square, too edgeless. He will be able to continue his ways unabated, and with the “This is not an exit” sign (this phrase is the last line of the novel as well) perched above his shoulder in the final monologue, it appears that he will do just that. Zuckerberg’s final action in The Social Network is staring at his ex-girlfriend’s Facebook profile, friend request still pending as he refreshes the page repeatedly. He has been sued by his friends and business partners and has paid out millions in settlements, but overall the damage was characterized by a member of his legal team as a “speeding ticket.”

Bateman’s final internal monologue (“I do not hope for a better world for anyone…but even after admitting this, there is no catharsis…this confession has meant nothing.”) even feels like it could have come from Zuckerberg. At the end of each film, neither has achieved internal peace, in spite of the likelihood that things will continue to go their way for the foreseeable future. It’s hard to imagine Facebook crashing and burning like tumblr or Vine, and it is likely that Bateman will be back to his murderous ways shortly. This is not an exit.